Women are participating in the labour force in greater numbers & earning more, but still face challenges & inequities. Breakdown & analysis.

We all know that women continue to face substantial hurdles in the quest for equal participation and pay; they are underrepresented in leadership roles, and there lingers an inequitable division of home responsibilities in a post-Covid world.

Atypical cultural investments like co-parenting bonuses to support men sharing household responsibilities and honest, transparent female-centred mentorship programs make improvement possible.

This report looks deeper into the cultural factors that exist in Canada, such as the ethnic disparities in pay, how beneficial a bachelor’s degree actually is for women, the household hangover from the pandemic, and how we can mend these persistent issues.

Women’s Workforce Participation

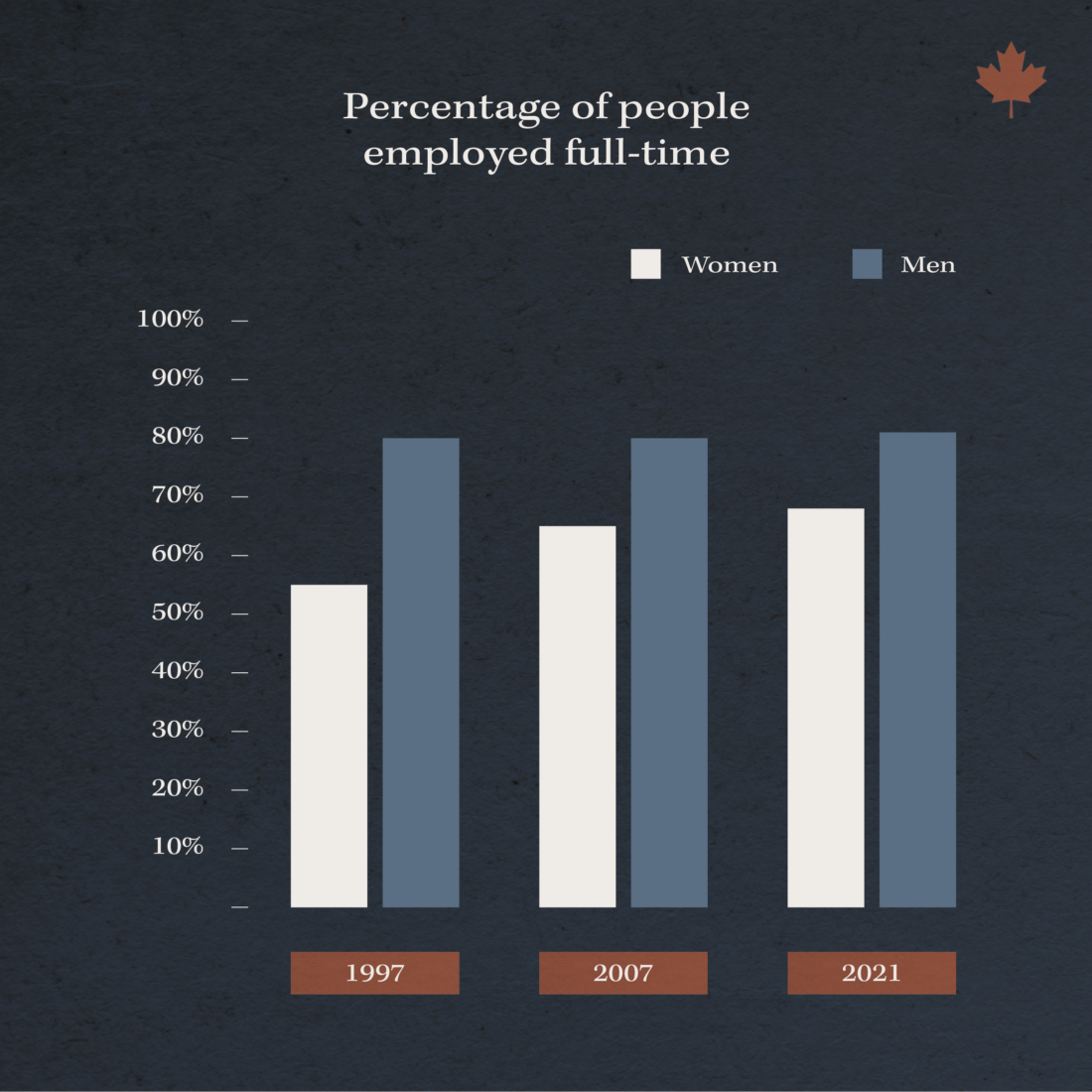

A Statistics Canada study looked at the evolution of workforce participation among core aged Canadian women (20-54) who were not full time students.1 It found that 68% of these women worked full time (30 hours or more per week) in 2021, up from 65% in 2007 and 55% in 1997. While the numbers show an upward trajectory, they remain well below male participation rates, which has held relatively steady at 81% during the same time period.

Ethnic Disparities in Full Time Work for Women

Ethnic discrepancies in workforce participation were also observed. The participation rate for non-Indigenous women born in Canada was 70%, while long-term immigrants (who have been in Canada for more than ten years) had a 65% participation rate. Indigenous women participated at a rate of 59%, matching that of more recent immigrants.1

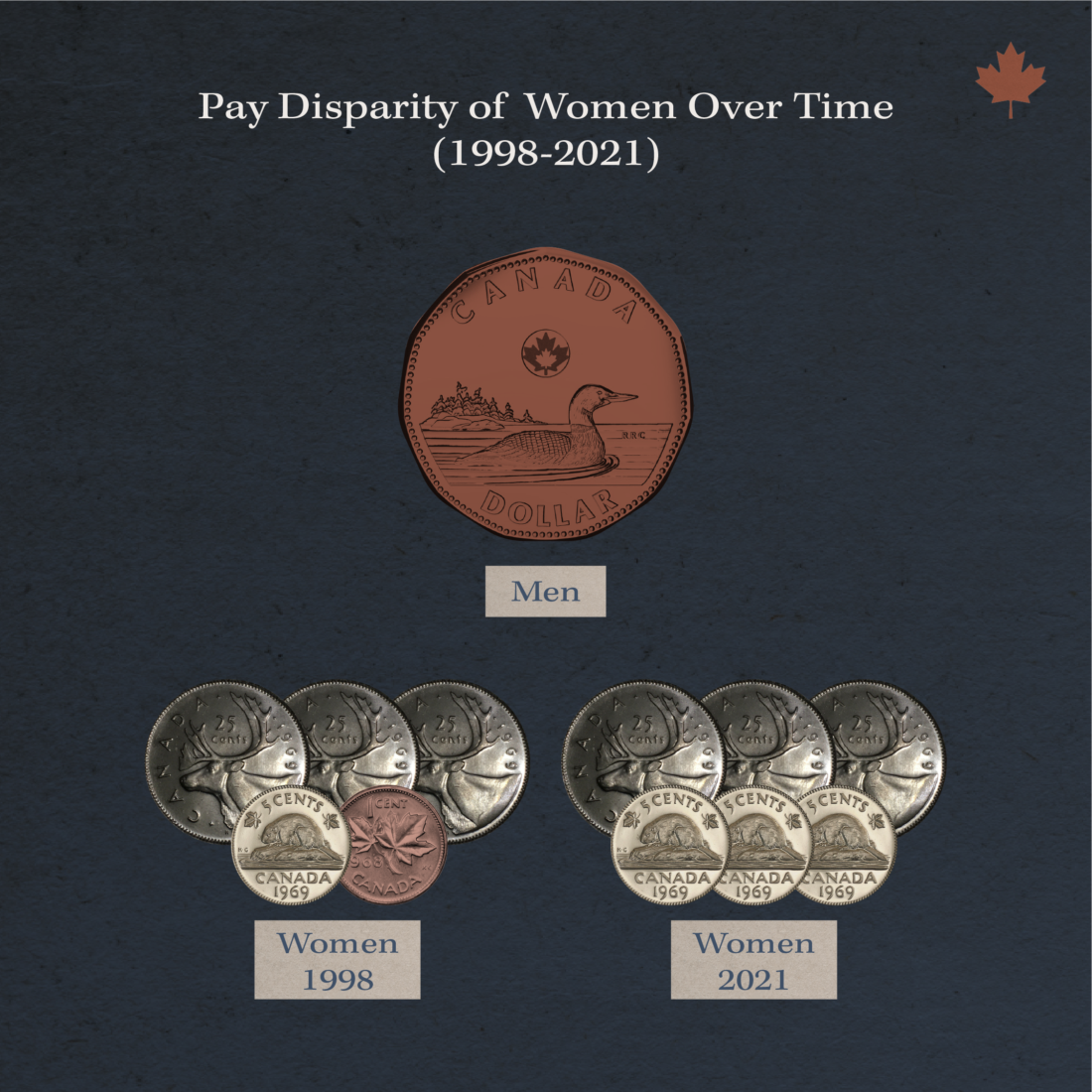

Another Statistics Canada study4 found that core aged women in Canada’s workforce earned 11.1% less than males in 2021. That gap has narrowed substantially since 1998, when the difference measured 18.8%, but still leaves an imperative for improvement.

Once again, the situation facing minority women is even more dire. Filipino women earned 74 cents for every dollar earned by women who were neither Indigenous nor visible minorities. Black women faced a pay gap of just over 16% when compared to the same control group. The earnings of Chinese women, meanwhile, were on par with non-minorities.

Uneven Impact of Bachelor’s Degrees

The study found that women in all groups were more likely to be working full time if they had a bachelor’s degree or higher.1 50% of recent female immigrants held at least a bachelor’s degree, compared with 38% of long-term immigrants, 36% of Canadian born non-Indigenous women, and 18% of Indigenous women.

The benefits of these credentials, however, seem to be uneven. 80% of Canadian-born women with bachelor’s degrees worked full time, as did 79% of Indigenous women. However, only 73% of long-term immigrants with bachelor’s degrees worked full time, with the number dropping to 62% for recent immigrants. This discrepancy is likely owing in part to the difficulty that immigrants face having their credentials recognized in Canada, an ongoing situation that has become something of a political hot-button.

Importance of Female Participation in Workforce

Countries that have greater levels of female participation in the workforce have an opportunity to boost their GDP, while of course contributing to the independence and economic stability of their female population.

Growth in this important metric can be fostered by prioritizing access to education, providing affordable childcare, and challenging long-established attitudes. Unfortunately, the International Labour Organization finds that 20% of men and 14% of women, globally, still believe it’s unacceptable for a woman to have a paid job outside of the house.3 Statistics like these highlight the task at hand.

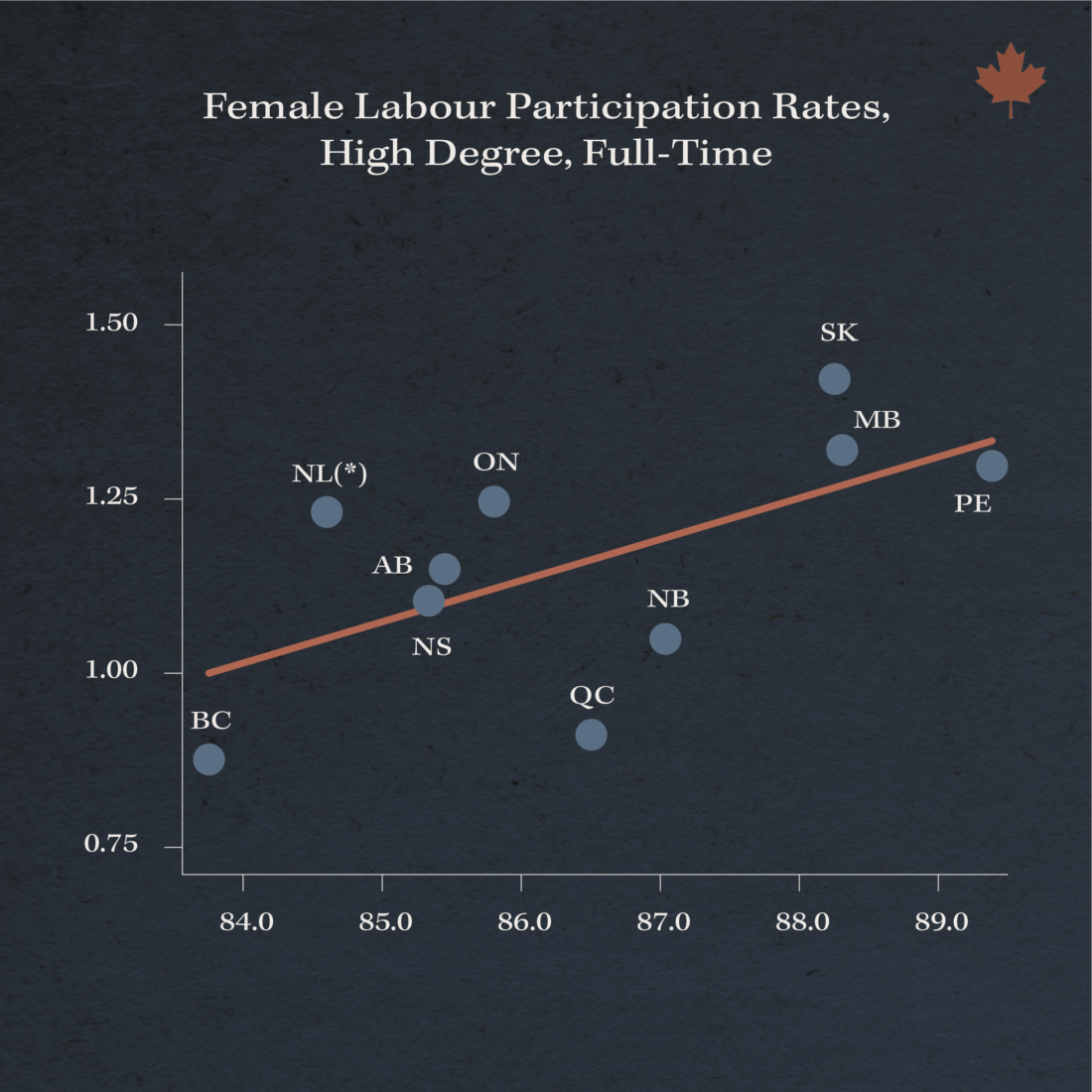

According to the IMF, female labour participation rates are positively and significantly correlated with labour productivity growth as shown in the graph below. 14

The Pay Gap

According to the Statistics Canada report, pay discrepancies are slowly narrowing, contributing to the slow erosion of the pay gap as a whole.

Some reasons stated for the narrowing gap are women’s increased educational attainment and a decline of the share of men in unionized employment.4

There are many ways of accounting for pay, but according to the Canadian Women’s Foundation, they all point to a problem.

“In general, the gender pay gap refers to the difference in average earnings of people based on gender,” reads their website. “It is a widely recognized indicator of gender inequities, and it exists across industries and professional levels. There are different ways of measuring the gap, but no matter how you measure it, the gap still exists.”5

Women Underrepresented in Leadership Roles (H2)

According to a recent Equileap study, there are more Canadian CEOs named Michael (7) than all female CEOs (6).6

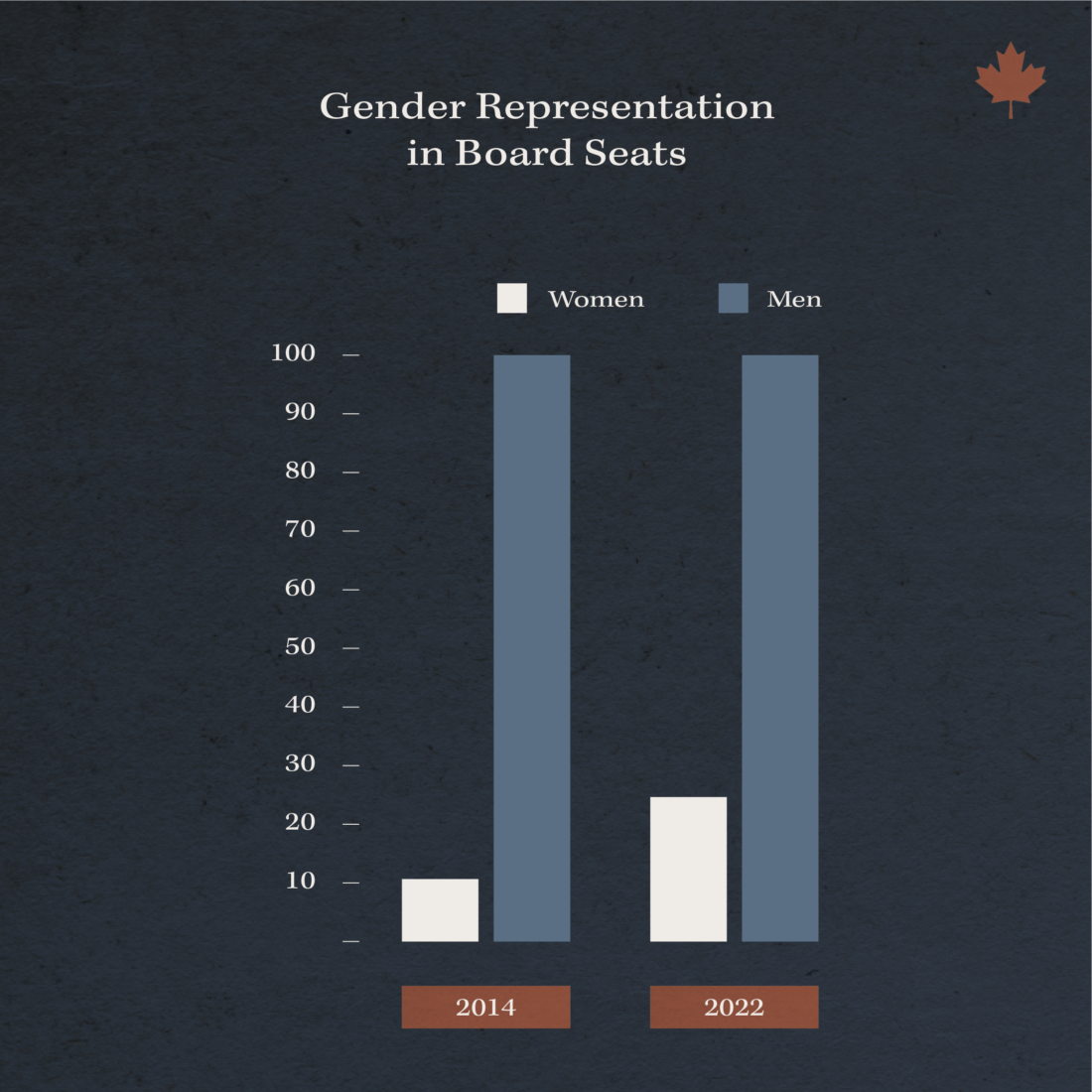

Another study released by the Canadian Securities Administrators shows that women occupy only 24% of corporate board seats in Canada.7 This number has risen from 11% since 2014 when the TSX instituted ‘comply or explain’ measures. The policy requires companies listed on the TSX to disclose their progress in getting more women around the board table, or explain why they cannot disclose that information.7

Women Passed Over for Promotions

Women are often seen as riskier hires and are not promoted to the same level or at the same rate as men.

Women are 30% less likely than men to get promoted out of an entry-level job, despite spending the same amount of time at a job. It is even more unlikely that women will move from middle management into executive roles, at a rate of 60% less likely than men. (https://canadianwomen.org/the-facts/women-and-leadership-in-canada/)

“Sexism still exists within our workplaces, and there are a lot of assumptions around gender that get made,” says Jillian Kilfoil, executive director of Women’s Network P.E.I. “Certainly, we know that although it’s illegal to pass up a woman with children for promotion, we know that informally, it does happen.”8

A study found that 17% of working parents say they have been passed over for an important assignment and 16% say they have been passed over for a promotion because they have children. Mothers are more likely than fathers to report each of these experiences.17

Interestingly, unconscious bias in the workplace can go back as far as the initial job posting for a company. The language used in the ad could be a great indication of whether a man or a woman is going to be hired for a role.

According to a report conducted by the ILO, if job descriptions for leadership roles are described with words commonly associated with the male gender, such as ‘dominant’ and ‘ambitious’, then male applicants may benefit from an unconscious bias in their favour, regarding men as a natural fit for the job, while the unconscious bias would work against women. 13

A report from McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.org found that women in leadership roles are not only more likely to have colleagues imply that they aren’t qualified for their jobs, but are also more likely to be mistaken for somebody more junior.7

Calgary-based tech company Benevity’s workforce is 54% women, a stat CEO Kelly Schmitt is proud of.

“Benevity never set targets to get here, but we do focus on behaviours that drive diversity,” she explains. “We hire women who are expecting, we promote women who are on parental leave, we have programs that give co-parenting bonuses to men who share parental leave with their partners.”7

The Benefits of Mentorship

One way to promote opportunity for female employees (or male employees, for that matter) is through formal mentoring programs. Studies show that employees who have a mentor are five times more likely to be promoted as those without.9 Even more shocking? The mentors themselves are six times more likely to be promoted!

Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations reports that minority representation at the management level can be boosted by up to 24% by mentoring programs.9

“Mentoring is a cooperative partnership that works best if there is candor and honesty on both sides,” writes career success expert Andie Kramer for Forbes. “Mentors should be cheerleaders for their mentees—providing encouragement, reassurance, and positive suggestions.”9

Work-Life Balance and the Unfair Distribution of Household Responsibilities

Compounding the problem for women in the workforce is the uneven distribution of household responsibilities. Women are often tasked with doing the heavy lifting when it comes to running a household and caring for children and aging relatives.

“These trade-offs can have long-lasting implications,” says Angie O’Leary, head of Wealth Planning at RBC Wealth Management–U.S. “Over time, women caregivers, even those in high-earning careers, experience a significant, negative impact on their income-generating capacity.”10

The result is the so-called “motherhood penalty”, which sees women’s earnings drop after entering parenthood. This stands in contrast to the “fatherhood bonus” that finds dads making more money after becoming a parent.5

Inequities Highlighted During Pandemic

61.5% of mothers with children under age 12 say they took on the majority or entirety of the extra care work, while only 22.4% of fathers report that they did. Mothers of children under the age of 12 were the demographic most likely to move from employed to not employed between 2019 and 2020 in member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 15

Women were also more likely to be employed as frontline workers when they were able to work throughout the pandemic, leaving them at a higher risk of exposure to the virus.16

While sectors previously dominated by women have suffered the most from pandemic-related job losses, the demands for unpaid domestic and care work have increased dramatically. This strain between women’s paid and unpaid work makes it more difficult for women to participate and succeed in the workplace, pushing some out of the workforce completely. 16

Work-Life Balance and Flexibility Are Key Equalizers

A positive trend in recent years is an increased focus on work-life balance. The pandemic showed that remote work was possible and flexibility quickly became a key benefit offered by companies recruiting talent. While it’s certainly not available to all, it’s a trend that many would like to see continue.

“We really need to think about our workplace cultures: How do we reimagine them so that we’re not just rewarding the ideal worker who can work all the time and act as if they don’t have caregiving responsibilities?” says author Brigid Schulte. How can we open up that sense of a whole human being, an authentic human being with work and life? How can we create work systems that provide opportunity for meaningful work — and yet don’t eat you alive, don’t burn you out?”12

While great progress has been made by women in the workforce, much work remains. As society re-examines old norms, the time is right to push for true gender equity in the workplace, both domestically and around the world.

Cited Sources

1 Drolet, Marie. “Full-Time Employment Is an Integral Part of…” Unmasking differences in women’s full-time employment. Government of Canada, Statistics Canada, September 26, 2022. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2022001/article/00009-eng.htm.

2 WorldBank. “Female Labor Force Participation.” World Bank Gender Data Portal. Accessed April 18, 2023. https://genderdata.worldbank.org/data-stories/flfp-data-story/.

3 “The Gender Gap in Employment: What’s Holding Women Back?” InfoStories. Accessed April 18, 2023. https://www.ilo.org/infostories/en-GB/Stories/Employment/barriers-women#persistent-barriers.

4 Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. “In the Publication Quality of Employment in Canada…” Pay gap, 1998 to 2021. Government of Canada, Statistics Canada, May 30, 2022. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/14-28-0001/2020001/article/00003-eng.htm.

5 “The Gender Pay Gap: Pay Gap in Canada: The Facts.” Canadian Women’s Foundation, December 23, 2022. https://canadianwomen.org/the-facts/the-gender-pay-gap/.

6 Saldanha, Ruth. “More Canadian CEOS Named Michael Than Women CEOS: Report.” Morningstar CA. Morningstar, Inc., March 2, 2023. https://www.morningstar.ca/ca/news/232320/more-canadian-ceos-named-michael-than-women-ceos-report.aspx.

7 Press, The Canadian. “Women Still Underrepresented in Canadian C Suites despite Small Gains – National.” Global News. Global News, November 18, 2022. https://globalnews.ca/news/9290070/women-c-suite-canada/.

8 Jenkins, Alison, and Local Journalism Initiative Reporter. “Women Still Not Valued Equally in the Workforce.” thestar.com. Toronto Star, March 2, 2021. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2021/03/02/women-still-not-valued-equally-in-the-workforce.html.

9 Kramer, Andie. “Women Need Mentors Now More than Ever.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, November 9, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/andiekramer/2021/07/14/women-need-mentors-now-more-than-ever/?sh=1655a09b2bbd.

10 “The Cost of Caregiving Falls Disproportionately on Women.” RBC Wealth Management. Accessed April 18, 2023. https://www.rbcwealthmanagement.com/en-us/insights/the-cost-of-caregiving-falls-disproportionately-on-women.

11 Barua, Akrur. “Gender Equality, Dealt a Blow by Covid-19, Still Has Much Ground to Cover.” Deloitte Insights. Deloitte, January 27, 2022. https://www2.deloitte.com/xe/en/insights/economy/impact-of-covid-on-women.html.

12 Gross, Terry. “Pandemic Makes Evident ‘Grotesque’ Gender Inequality in Household Work.” NPR. NPR, May 21, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/05/21/860091230/pandemic-makes-evident-grotesque-gender-inequality-in-household-work.

13 Breaking barriers: Unconscious gender bias in the workplace (2017) International Labour Organisation. August 2017 https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_dialogue/—act_emp/documents/publication/wcms_601276.pdf

14 Ishi, K., Mariscal, R. and Petersson, B. (2017) Women are key for future growth. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WP/2017/wp17166.ashx

15 ‘Caregiving in crisis: Gender inequality in paid and unpaid work during COVID-19’ (2021) OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19) https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=1122_1122019-pxf57r6v6k&title=Caregiving-in-crisis-Gender-inequality-in-paid-and-unpaid-work-during-COVID-19

16 The lasting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s work, health, and safety (no date) Wilson Center. Available at: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/lasting-effects-covid-19-pandemic-womens-work-health-and-safety 17 Fast facts: Mothers in the workforce (2020) AAUW. Available at: https://www.aauw.org/resources/article/fast-facts-working-moms/ (Accessed: 16 May 2023).